Elsie Maria Sophia Lombard was Barbara Croeser’s mother. In 1826, she and her husband, Jacobus Marthinus Croeser went to live in Cape Town with his father. In 1828, the same year her last (fifth) child was born, she applied to the Supreme Court to separate them “from bed, board and community of property and to direct that their Estate may be administered …..by Trustees.”[1] The details of her husband’s behaviour towards her do not make pleasant reading. In pursuing her husband through the courts in this way she must have been at odds with current thinking in the conservative, Dutch Reformed community in Malmesbury. This provides some justification for further examination of the Lombard family, its values, and perhaps also its genetic predispositions. Of particular interest is the history of a formidable ancestor, Groote Catrijn of Palicut.

Let us start the account with Elsie Maria Sophia’s non-slave ancestors, Pierre Lombard and Marie Couteau. They arrived in the Cape in 1688 as Huguenots on the ship Borssenburg. They settled in Drakenstein, acquired various farms and had six children among whom was their son, Anthonie (born 1693). Anthonie married Johanna Snyman (born 1699) and this is where the history becomes interesting. It was Johanna Snyman who had slave ancestry.

Johanna Snyman’s mother was Marguerite-Therese de Savoye whose family were Huguenots from Belgium. They arrived in the Cape in 1688 when Marguerite-Therese was 17 years old. Like many other Huguenot families, they also settled in Drakenstein and attended the local Dutch Reformed Church. Marguerite-Therese goes down in South African history as being the only European to marry, in 1690, Christoffel Snyman, the son of a freed slave.

Here some context is needed. When Jan van Riebeek settled in the Cape there was a desperate need for labour to establish the agricultural industries and to fulfil many other service roles. With its headquarters in Batavia (now Jakarta), the Dutch East India Company had long relied on the service of slaves from India and countries bordering the Bay of Bengal. These were the slaves who first came to the Cape. In the early years of the Cape settlement, with a small population there was an imbalance between the sexes. Men outnumbered women among both settlers and the slaves. The slaves were no longer in contact with their homelands and readily assimilated culturally. A small number of slaves were freed by their owners, a very few bought their own freedom. Interrelationships between the Dutch and their slaves became common, even obligatory, and the position of children from these liaisons was open to negotiation, sometimes punitive, sometimes generous. The Cape was “a melting pot”. [2]

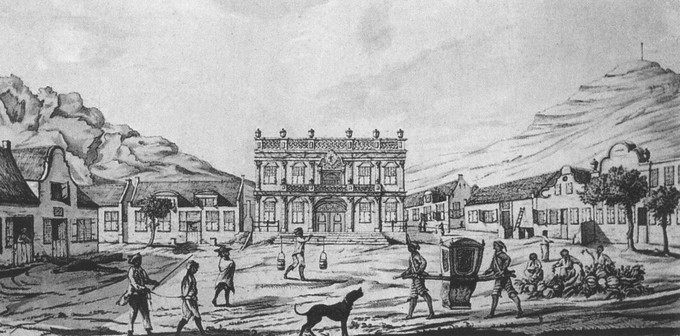

Johannes Rach, Greenmarket Square, Cape Town, 1762. From the Western Cape Archives and Records Services. Nigel Worden, Slavery at the Cape

When tracing slave ancestry in the Cape, there are some documents that establish formal relationships but often we are forced to speculate[iii]. So it is with Christoffel Snyman. It is generally accepted that he was the son of a slave, Groote Catrijn (Big Catherine) who was born in Palicut on the East Coast of India in about 1631 and ended up as a slave, of Muslim origin, in Batavia. Here she was involved in a violent confrontation with another slave who was her lover. Assaulted and thrown to the ground she grabbed a cobblestone and aimed, hard, for his genitals. Instead she hit his lower stomach, rupturing his bladder. Four days later he died. She was found guilty of murder and sentenced to be tied to a stake and garrotted. Two days later her sentence was commuted to banishment as a slave to the Cape. She arrived in 1657.

It is fair to say that in the Cape, while employed as a washerwoman in various households, she lived by her wits, engaged in numerous dubious activities. She renounced her Muslim faith and, very unusually for a slave, was baptised in 1668. She had a sexual relationship with a Dutch soldier, Hans Christoffel Snijman who was constantly breaking the law and running foul of the authorities. Finally he disappeared from the scene. In 1669 Groote Catrijn presented a son, Christoffel, for baptism with the surname of Snijman.

In 1671 Groote Catrijn married a free slave Anthony of Bengal (himself baptised in 1670). Anthony was a shining success as a slave, buying his freedom and establishing productive farming in the Cape. He took on her children, including Christoffel Snijman. (In some genealogies Anthony of Bengal is named as the boy’s father) In 1672 Groote Catrijn was finally and formally pardoned and freed from slavery. Anthony of Bengal did well despite economic ups and downs. In 1682 they are mentioned in the Muster Roll of the Cape as follows:

- Antony van Bengale: 1 man;

- Catharyn van Palikatte: 1 wife;

- 1 son [Christoffel Snijman];

- 1 daughter [Petronella van Bengale]

- 3 male adult slaves [Paul van Malabar, the Malay Baddou [van Bali?] & NN];

- 2 male slave children [names unknown]

- 2 horses; 3 cattle;

- 39 sheep;

- 12 pigs

- 1 muid wheat sown; 7 muids wheat reaped

- 2 flintlocks; 1 rapier

With the exception of Christoffel Snijman, the family died, one after the other, from an unknown cause in about 1683. Christoffel was the sole heir of the estate. He was well-provided with an education and financial resources for his life with Marguerite-Therese de Savoye in Drakenstein. The two of them and their many children did well. Christoffel Snijman died in 1705 and Marguerite-Therese (known now as Margo) appeared on the tax roll for 1705 as follows:

- Wed: [uwe] Christoffel Snijman

- 1 son; 6 daughters;

- 4 adult male slaves; 1 adult female slave

- 3 horses;

- 20 oxen;

- 40 cows;

- 10 calves;

- 10 heifers;

- 300 sheep;

- 10 pigs

- 60 vines

- 6 leaguers wine

- 15 muids barley sown

- 15 muids barley harvested

- 3 muids rye sown

- 25 muids rye harvested

One of those daughters was Johanna Snyman who married into the Lombard family and became the great-grandmother of Elsie Maria Sophia Lombard.

As can be seen these former slaves became slave owners themselves. From this brief history we should not draw the conclusion that slavery was a benign practice. Rather it points to both Groote Catrijn and Anthony of Bengal having enormous commitment and skill in negotiating their way to freedom. The fate of other slaves remained mired in sad degradation. The early years of the Cape under the Dutch East India Company were focused on trade and there was a more open approach to interracial marriages especially with slaves from the East, although it was never openly sanctioned.

As the Cape prospered during the 1700s and the colonial era dawned, the numbers of slaves increased, many now coming from Africa and Madagascar. The 1800s also saw a substantial increase in the number of European immigrants. This was particularly true after the demise of the Dutch East India Company and British occupation and administrative control of the Cape. With these changes came a greater awareness of, and attention to racial differences.

The 1833 Slavery Abolition Bill

passed by the British government lead inevitably to economic disruption and a

racially segregated social life in the Cape. The emancipation of slaves by Britain therefore

did not resolve but rather intensified the problems of different races who

could not melt into each other – as they had done in the past.

[1] NAAIRS KAB database CSC Vol 2/6/2/3. MOTION. MEMORIAL OF JACOB MARTHINUS CROESER AND ELSJE MARIA SOPHIA CROESER (BORN LOMBARD).

[2] See H.F Heese, 1984, Groep sonder Grense (Die rol en status van die gemengde bevolking aan die Kaap, 1652-1795). Belville: Wes-Kaaplandse Instituut vir Historiese Navorsing.

[3] I have relied heavily on the research done by Mansell G. Upham, Cape Mothers Groote Catrijn van Paliacatta (c. 1631-1683), her slave Maria van Bengale & her daughter-in-law Marguerite-Thérèse de Savoye (1673-1742) in Uprooted Lives: Unfurling the Cape of Good Hope’s Earliest Colonial Inhabitants (1652-1713. Remarkable Writing on First Fifty Years http://www.e-family.co.za/ffy/ui45.htm.© Mansell G Upham – pdf on http://www.e-family.co.za/ffy/RemarkableWriting/UL14CapeMothers.pdf